Hiking an Underground River in Mexico

An underground river – I didn’t know such a thing existed. But ok, it made sense. A river underground, right? Want to hike it? Sure, why not?

I imagined a winding tube starting from a modest crack in the earth, like an old-time mine shaft cut through rock. I imagined crouching and crawling, like when my middle school buddies and I explored a city sewer. My friend Pedro, who invited me, said it would take about six hours. Alright, let’s do it.

I definitely didn’t imagine a fast-flowing, waist-deep stream entering a huge vertical hole wider than the tunnel for a two-lane mountain highway. I didn’t expect to spend more than eight hours underground, to finally emerge at sunset from an equally large hole on the other side of a mountain. And I didn’t expect that, before all of this, we’d hike for two hours and then climb down a steep canyon cliff on a flimsy steel staircase just to get to the cave entrance.

About 150 kilometers southwest of Mexico City in central Mexico, the Chontalcoatlán River begins on the high slopes of the inactive Nevado de Toluca volcano. It travels though parched, desolate highlands of thick shrubs, scraggly trees, and tall cactus.

Above ground, it looks like a typical mountain stream. Cold clear water flows over submerged boulders and rocks, twisting and turning at the bottom of a dry valley so deep that you’d never see it unless you peered down from a bridge.

This large region of the Sierra Madre del Sur mountain range is neither cool plateau nor steaming valley, but something in between, a subtropical land of sand, sandstone, and tiny communities of concrete and sweat. These are the hidden corners of Mexico, far from cities or even proper towns. These are the corners that hide underground rivers.

The word Chontalcoatlán is a mouthful, so it’s often abbreviated to La Chonta. It’s named after the Chontal tribe, one of the many indigenous groups of central Mexico with distinct customs and languages. Currently fewer than 200 native speakers of Chontal remain, most living far away in the southern state of Oaxaca.

We began the adventure at the Grutas de Cacahuamilpa — the Cacahuamilpa Caves — a national park with chambers as big as soccer stadiums. A concrete footpath takes visitors deep underground into one of the largest cave systems in the world, so large and labyrinthine that native people hid in them after the Spanish conquest.

If you’d like to visit the Cacahuamilpa Caves in Mexico, you can take a cave tour from Mexico City, a cave tour from Taxco, or a cave tour from Acapulco.

Below the entrance to Cacahuamilpa’s cave passage is where the Chonta river exits the mountain, returning to daylight. At this same point another underground river, San Jeronimo, flows out of an equally large hole and joins the Chonta to form the Amacuazac River. It then makes the long trip to the Pacific Ocean.

These two holes are called Dos Bocas (Two Mouths), and they’re easily reached by hiking down the valley from the entrance to the Cacahuamilpa Caves.

At 12 km, the hike through the underground portion of San Jeronimo is not only longer but also much more treacherous than the eight kilometers La Chonta spends below ground. San Jeronimo is for experts only. Pedro told me that some sections of the underground river have whirlpools that can suck you down into who-knows-what below, lifejacket and all.

Seven of us would hike La Chonta today: Pedro, three of his co-workers — our leader Carlos and two others — and Carlos’s teenage son and his son’s friend.

Pedro and a few of the others had done the hike before, but Carlos was our leader because he’d done the hike almost every year for the past 20 years. His first time was with a high school group.

After breakfast in the small market at the entrance to the Cacahuamilpa Caves National Park, Carlos hired a pickup truck to take us to the trailhead high in the mountains. We would exit the underground river at Dos Bocas right next to Cacahuamilpa, but first we’d need to get to the opening of the cave, by truck and then on foot. I knew the highway well, having ridden it on my bicycle many times, but I’d never noticed the small turnoff about 15 minutes by car from the caves.

We hiked for about two hours, first along a mountain ridge though a forest of leafless trees and shrubs. It was dry season — the reason we were going in February. The hike is impossible during the summer rainy season when the river and rapids are high.

Carlos and his friends chose early February to beat groups of students and boy scouts who leave their garbage inside, which the summer rains eventually wash away every year. At one point in the cave I saw a car tire stretched and jammed down to the bottom of a long, pointy piece of rock, a testament to how powerful the river is during rainy season.

I wore a swimming suit, a quick-dry t-shirt, a lifejacket, and stiff-soled hiking boots. I was glad for the boots many times that day, even though one of them eventually fell apart. A few people in our group had tennis shoes, and I often saw them wince as they bashed their feet on submerged rocks. Even with hiking boots, my feet and ankles were brutalized by the end of the day.

I also carried a small backpack that held two headlamps, two sandwiches, and a bottle of water. Slung to the backpack was an old bicycle helmet that I’d wear once in the cave.

We crossed the high ridge of the mountain range and began to descend. The trail got steeper as it curved downward, with large stones in the path among the sand. The trail entered the morning shade of the valley and suddenly the trees were full of green. Soon we were crawling over boulders and gripping branches for support. The trail ended at a cliff. A thick metal cord, lightly rusted with age, was bolted to a rock above the cliff.

Carlos climbed down first, disappearing below the rocky ledge. Then one by one we went down. I was the second to last. The metal cord held firm and there were plenty of footholds.

As I stepped down the cliff, Carlos came into view below. He wasn’t on the valley floor, but on a narrow ridge above another cliff. From here an old metal ladder began that was much longer than the cord. Halfway down it too went out of sight under the cliff.

The ladder shook and shifted as I climbed down it. A few rungs were missing, broken away. While placing hand below hand, foot below foot, I thought about Pedro above me, waiting until I got to the bottom before he started climbing down.

I thought about the large group we’d passed earlier on the trail. They’d climb down next, all ten or so of them, one after another. And after them more groups would come during the two or three months of continuing dry season.

They’d all make it down. The ladder would hold. And with that, I landed. My feet were firm on the rocky riverbank. For the first time I had a clear view of the humungous hole and thought, wow.

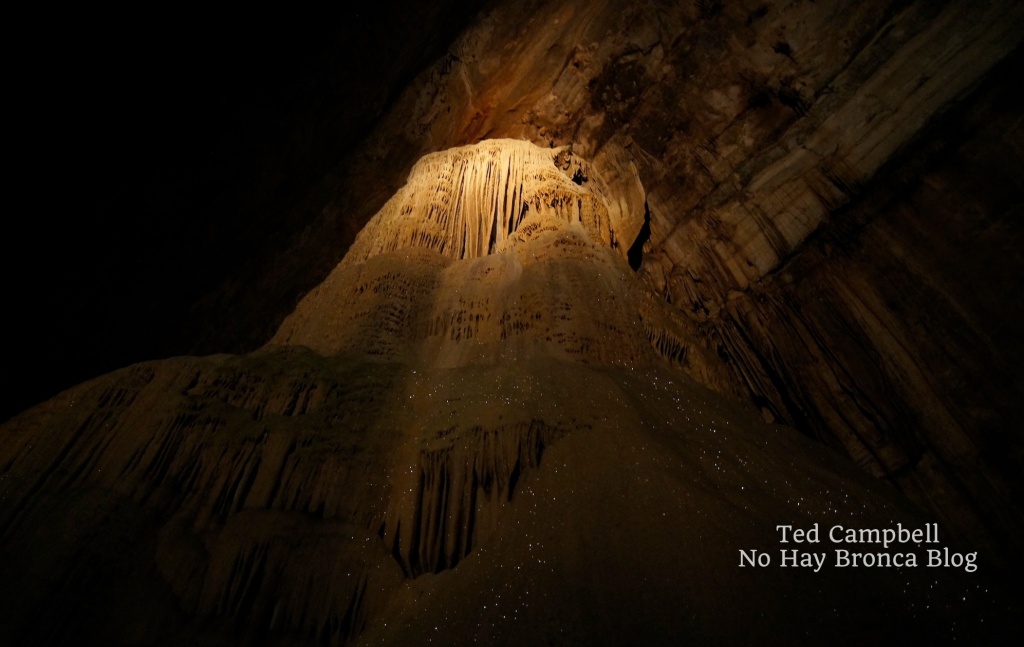

The opening to the underground river was a vertical crater rimmed in white with sheer cliffs above. You could see that, instead of continuing on between the mountains, the forces of water that had formed this deep valley — I’d call it a canyon or gorge if it weren’t so covered in shrubs and trees — hit a dead end here. Somehow the crater was hollowed out, sucking water into it like the drain on a locker room floor.

We sat under the high cliffs and had an early lunch before entering. The chamber at the opening was large as an airplane hanger, with calm water below that flowed into total darkness.

The shakiness I felt from climbing down the adder finally left me. I half-expected to jump right in the water and start floating downstream, but instead we walked on the sandy banks, climbing over boulders strewn about. It didn’t take long until the faint light from the big hole behind us finally disappeared and the only light was from our headlamps and flashlights.

When we came to impassable cliffs, we’d wade across the underground river to the other side, initially going no deeper than our thighs. The water was cold. When the current ran quickly, we’d all hold hands as we stumbled across.

Carlos was always in the lead, picking the best route. He told me later that nothing was as he remembered it. The two powerful earthquakes that shook central Mexico in the fall of 2017 had moved everything around.

(I finally got around to posting this story in 2023 but did this hike in 2018.)

The cavern walls and ceiling were covered with intricate limestone structures. Delicate ridges of sparkling mini-crystals dripped like melted cheese frozen to stone. False turns in stagnant pools of water had thick films of brown and green that released a rotten stench as we waded through them. We stopped at one point and turned off our flashlights. The darkness was complete—you couldn’t see your hands in front of your face.

After several hours of this we reached a chamber so big that the flashlight beams vanished overhead. We stood on a wide gravel beach. Next to the cavern wall was a foot-tall statue of the Virgin Mary in a metal cage, decorated with colorful plastic flowers and surrounded by the remains of burnt candles. The metal cage was deeply rusted and the statue was coated in black soot from the candles.

Nearby on the rock was a large plaque in recognition of one of the underground river’s early explorers, who’d recently died of old age, not in the cavern as I first assumed. By how worn it was, the plaque looked ancient, but it had been erected only five years earlier.

Carlos said there were interesting places to explore here. We walked across the gravel and scrambled up some boulders. We took off our lifejackets and backpacks, leaving them on the rocks. A rope hung down from a cliff. We took turns climbing up into the dark unknown.

At the top of the cliff was a flat platform of smooth stone. The ceiling was still far above and out of flashlight range, even though we’d already climbed higher than a two-story building. We walked around a corner to an area enclosed in high walls of jagged stone. Pointy, delicate stalactites hung from above. Carlos shone his headlamp down to where the cavern wall met the floor, into a hole no bigger than the opening of a washing machine.

“We can climb in there,” he said, getting on his knees. He adjusted his headlamp and crawled in headfirst, slithering like an iguana, his boots dangling behind as he pushed himself into the hole.

His son went next. Then me. The ground was heavy mud that protected my elbows and knees from the hard rock, although they were unavoidably scratched a few times. Occasionally I could lift my head and look around, but in most parts the rock was so close that my chin dipped into the mud below and my helmet banged against the rock above.

The tiny tunnel went up, then to the side, then down, then up again. One downward section was a steep slide headfirst into the mud. It was more open at the bottom, and I could get up on my knees. Carlos’s son sat there with the mud above his hips, eyes wide, breathing hard—clearly terrified.

“I’m going back,” he said. He called down the cave to his father, “I’m going back.” I couldn’t hear Carlos’s muffled reply. His son squeezed passed me and scrambled up the rock I’d just slid down.

That’s when I felt it—the closeness of the walls, the staleness of the air, the feeling of being utterly trapped and helpless. If I panicked, then I’d be truly trapped—there was no rushing out of this cave. The only way out was a slow, patient crawl through even tighter rock, following Carlos’s son. I took a deep breath of the muddy air, reminding myself that panic was the only enemy. Or another earthquake…

It was warm, at least. I wasn’t shivering for the first time since getting into the underground river hours ago. Calm, I told myself, be calm. At that moment Pedro came down the slide and splashed into the mud next to me.

“I’m going back,” I said. “Ok,” he replied. He squeezed past me toward Carlos deeper in the cave.

I looked at the soles of Pedro’s boots slipping out of sight, then in the other direction up the slide toward the exit, then back at the hole where Pedro’s boots had been. Ah, what the hell, I thought, and followed him.

We crawled about twice as deep again to another chamber, this one as spacious as the bathroom on a Greyhound bus. Carlos was waiting for us there. He pointed to where the cave continued on the high opposite side of the chamber. It would be the tightest squeeze yet.

“After about two hours, it reaches an underground lake,” Carlos said.

“You’ve been to the lake?” I asked.

“Sure, many times.” He pointed to a crude clay sculpture of a man with a large erect penis on one side of the chamber. “My friends made that the first time I came down here, when I was in high school.”

“Two hours?” I asked.

“Yes, about two hours. We can’t go now, not enough time. We can do it next time.”

“Two hours in a tunnel like this one we just went through?”

“Most of it’s even smaller,” he answered.

An underground lake. Where? Why? How? It wasn’t part of the river, it was just there. What an incredible sight. I imagined spending two more hours in this tight passage with its tight air. Would I make it? That was a question for another day.

We turned around and started crawling out. The claustrophobia stayed with me, lingering on, but at least I knew where I was headed.

Squeezing into the cold air felt like being born, or more accurately, considering all the mud, defecated.

We were coated from head to toe. The ones who hadn’t gone in the hole stood around rubbing their hands together for warmth. Two hopped up and down, shaking off drops of water. They’d been waiting all the while we crept deeper underground and were still soaking wet. Using the rope, we climbed down the cliff and rinsed off in some rapids.

We spent the next hours scrambling over tall rocks on the riverbank, trekking over gravel mini-beaches, and wading across the underground river when necessary. Now it was often deep enough that we finally went in up to our lifejackets, but we could usually still touch bottom. The cavern turned and twisted with the river, sometimes opening into high chambers, but never anything close to as large as the one where we’d stopped.

All of a sudden, an eerie glow appeared downstream. It grew larger as we approached. We took a turn and there it was, a massive hole in the earth far above the biggest chamber yet.

This was the second entrance to La Chonta, an opening called the Hoyanco del Chanchuyo (Chanchuyo’s pothole), aka la Ventana (window) or Claraboya (skylight). At roughly the halfway point of the underground river, this is a common entrance for explorers with less time or ambition than us.

It’s also a popular rock climbing spot because of the many routes on the high side of the hole. From the river it looked like the passageway from the underworld back to the living world.

Thick beams of sunlight shone into the open cavern. Here the underground river ran around big boulders and though sections of fast rapids. We sat on a section of rocks not coated with swallow droppings, ate our remaining food, and rested for about 30 minutes, while watching two people carefully scramble down the slopes from above.

Once we started hiking again, full from the food but cold from the inactivity, it didn’t take long for all the light from the hole to vanish, after only a few twists and turns. The cave was narrower here, about as big around as a subway tunnel. The smaller space meant fewer gravelly banks, bigger boulders, and deeper water. So during these final three or four hours we spent much more time in the water. It was usually deep enough that we had to swim.

To protect our knees from submerged boulders, we held our feet in front of us as we floated downstream, paddling with our hands. It was cold but a nice change from constantly slipping and scrambling in boots heavy with sand and water. Near the end I was so exhausted that the freezing water felt like a wonderful feather bed all around me. The cold became a comfort.

In some sections, there was no riverbank at all, just sheer walls on both sides. I often held Pedro’s hand through these. He couldn’t swim, although he floated in a lifejacket well enough. But when the current picked up, or when we started bumping into underwater rocks, the motion would flip him over, submerging his head. He’d struggle to float on his back again, splashing in the black water.

Each time I could see the fatigue in his eyes, along with something else—not fear, more like dread. But then, each time, his eyes would meet mine, his face would break into a smile, and he’d lift his hand and give me a thumbs-up.

Another light appeared before us. The exit, finally. Bats and swallows swarmed overhead. Warm fresh air flowed into the hole. Peering over the boulders, I saw the green of trees and shrubs. Green meant life, and life meant escape.

We pulled ourselves out of the water, panting and dripping in the half-light. Carlos scrambled over piles of stone on both sides, looking for a route out, and announced that we’d have to float out. The routes he remembered were gone.

So we floated down the rapids, first under the high cavern roof and then under the big blue sky, with tall overgrown valley walls on both sides. The water was a muddy brown, and it seemed even colder in the open air. We reached a sandy bank and looked to our left at another hole, equally large—the exit for the San Jeronimo River. We’d made it.

The sun began to set by the time we’d knocked the sand from our boots and poured the water out of our backpacks. The concrete path from the river up to the national park entrance was steep and long, but easy compared to everything else we’d hiked that day. The ground was solid, at least, and dry. By now, the sole of one of my boots had come loose. It flopped loudly with a slurping sound of water as I hiked uphill.

It was dark when we made it to the empty parking lot, where we changed clothes in a bathroom. We began the long drive back home, with a stop for tacos of course.

Hiking a subterranean river wasn’t what I expected. Besides excitement and adventure, there was awe, fear, and exhilaration unlike anything I’d ever experienced. In the tightest tunnel, it was a rush of claustrophobia, and in the biggest chamber, it was a reminder of the ant-like insignificance of the individual human.

It was also a lot of fun. And a big part of that fun—a big part of that awe—was the glimpse into the deep, dark, mysterious world below us. Once you get that glimpse, it’s unforgettable.

IF YOU WANT TO GO

Unless you’re fortunate enough to be invited by friendly and experienced locals, like I was, you’ll need to find a guide. Don’t attempt the trip by yourself. You’ll get lost, if not in the underground river then on the hike to get there.

The trail to the entrance of the underground river has many others branching off from it, and of course the underground river itself moves through total darkness with countless possible routes and dead ends.

If you find a guide and are going into the underground river, wear hiking boots. You may end up ruining your boots like I did, but that’s better than ruining your feet.

Whatever you bring, pack it in several waterproof cases. If you bring a camera, carry it in a hard case, or risk it being bashed on the rocks, like your knees and elbows.

The time to hike through the underground river is the dry season in spring, particularly March and April.

The nearest town is Taxco, which is one of the most beautiful small towns in Mexico. Its colonial-era buildings, all painted white, are scattered over mountain slopes and connected by twisting cobblestone streets and narrow alleys.

Taxco isn’t far from Mexico City and it’s a good place to inquire about the Chonta hike. If nothing else, from Taxco you can easily visit the Grutas de Cacahuamilpa National Park and its enormous, impressive chambers. Be sure to hike down the valley to check out Dos Bocas, where the two rivers flow out of the mountain.

Recommended Mexico Cave Tours

There are many caves in Mexico you can explore. Please note that these Mexico cave tours don’t go through the underground river that I described in the story above, but a few of them go to the Grutas de Cacahuamilpa National Park, which has some of the best caves in Mexico.

You can take a Cacahuamilpa cave tour from Mexico City, Taxco, or Acapulco.

The easiest and most affordable way to get to Cacahuamilpa is from Taxco. Click here for more information about this Mexico cave tour.

You can also do a Cacahuamilpa cave tour from Mexico City. On this 11-hour trip, you’ll explore Taxco after spending some time in the Cacahuamilpa caves.

A third option to visit Cacahuamilpa is from Acapulco. This 7-hour Mexico cave tour also takes you to some interesting attractions in Taxco.

Perhaps the most famous caves in Mexico are the Tolantongo Caves. Tolantongo aren’t only caves, but also hot springs. Click here for information about a Mexico cave tour to the Tolantongo Caves.

Chiapas also has some of the best caves in Mexico. If you’re in San Cristobal de las Casas, check out this Mexico cave tour to three places: Arcotete, Mamut & Rancho Nuevo.

Finally, some of the best Mexico caves are the cenotes of the Mayan Riviera. Scuba diving in cenotes is absolutely one of coolest things I’ve done in Mexico, right up there with the underground river hike I described in the story above. Click here for a good cenote tour that also stops at the Mayan ruins of Tulum.

This page contains affiliate links, which means I earn a small commission if you purchase something after clicking a link on this site. I receive this commission at no additional cost to you.

All about Beer in Mexico: The Mark of the Michelada

Beer in Mexico: Mexican domestic beer, microbrews, and beer-drinking customs

Beer lovers, Mexico’s got you covered.

Beer in Mexico has tons of variety and quality. Popular domestic Mexican beer brands are inexpensive and available everywhere. The average convenience store has at least six options, ranging from smooth pilsners to amber-colored ales.

Factory beer stores called depositos offer even lower prices. You can find a reasonable number of imports, and there’s even a growing microbrew scene—some not so good, most overpriced, but at least the options are there.

There’s a long history of beer brewing in Mexico, beginning with the Spanish in colonial times and later greatly improved by several waves of German immigrants to Mexico in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Cuauhtemoc-Moctezuma, one of the two major Mexican beer brands, was cofounded by German immigrants, and Mexico’s many dark beers from both companies are largely based on German recipes.

Germans didn’t only bring better brewing techniques, but also music. Polka directly influenced popular Mexican styles like banda, which features large horn sections, tuba for bass, and bouncy 3/4 rhythms. And what goes better with banda than a cold beer or ten?

Before beer, the alcoholic drink of choice in Mexico was pulque, made from the fermented nectar in the heart of the large maguey plant, similar to how tequila is made from the blue agave. Unlike tequila or other local spirits like mezcal, pulque has roughly the same alcohol content as beer.

White, milky pulque has a slightly pungent or sour yet somehow refreshing taste, unless it’s curado—brewed with an additional natural flavor, such as strawberries or pine nuts.

Pulque was the victim of a smear campaign by breweries in Mexico in the early 20th century that portrayed it as a drink for low-class people with bad taste, giving it a negative stereotype that persists today, despite a slow-growing hipster renaissance.

Pulque is still widely believed to be brewed with cow manure, which isn’t true, at least according to all the pulqueleros (pulque brewers and sellers) I’ve bought from and drunk with.

What is true is that pulque can’t be bottled; seal it, and it will eventually explode, due to pressure from ongoing fermentation. The best place to try pulque is at a pulquería or pulqueta (a cantina serving pulque—check out Tenampa and other spots in Garibaldi Plaza in Mexico City, where all the mariachis are) or in a small town’s outdoor Sunday market, where you’ll see people, mostly men, gathered around a big plastic jug drinking pulque from earthenware mugs.

But enough about polka and pulque—on to beer in Mexico.

Domestic beer in Mexico

Domestic beers are so well-established that you don’t see too many imports. The most common ones are probably Heineken, Stella Artois, and the occasional Budweiser. And recently, Michelob, which is strangely being marketed as an upmarket beer in Mexico. You’ll find that imports are more expensive than the typically better Mexican equivalent, especially in cantinas and restaurants.

Domestic beer in Mexico is divided into two broad categories—clara and oscura, which mean light and dark. Claras are lagers or pilsners, like Budweiser or Heineken. Oscuras are usually ales, sometimes bocks, although the recipe and brewing method usually isn’t specified, other than simply being “dark.”

There are two major Mexican beer brands, which like Miller and Anheuser-Busch in the U.S. have slowly acquired most other independent breweries in Mexico. Both companies have their light and dark brews, with good ones on both sides.

Grupo Modelo is best known for Corona, and also produces Victoria beer, Modelo, Negra Modelo, Pacifico, Montejo, Leon, and Barrilito. This is the top Mexican beer brand, although it’s been owned by Anheuser-Busch since 2013.

The other Mexican beer brand is Cuauhtemoc-Moctezuma, owned by Heineken and named after two important Aztec leaders during the Spanish conquest.

History has been kinder to the former than the latter. While there are statues of Cuauhtemoc throughout Mexico, and countless neighborhoods and children named after him, Moctezuma is regarded as more of a failure, a weakling who was manipulated and outmaneuvered by Hernan Cortes.

Despite this, his image is featured on the label of one of Cuauhtemoc-Moctezuma Brewery’s most important beers, Indio, which means “Indian.” Their other brands include Sol, Tecate, Dos Equis, Bohemia, Superior, Noche Buena, and Carta Blanca.

These domestic beers are available all over Mexico, with some more popular in certain regions, such as Tecate in the north or Superior in the south.

Note: I prefer dark beer, especially porters and stouts. I also love a good pale ale; IPAs, not so much, and weiss beers don’t do much for me. Light beer like Miller High Life or Corona are fine, but taste quite similar to me, especially when you squeeze a lime into them, as Mexicans are prone to do.

So, instead of saying which are “best,” I’ll just describe them and tell you what I like.

Oscura: dark beer in Mexico

As mentioned, dark beer in Mexico falls under the general category of oscura. They’re mostly ales. Really dark beers like porters and stouts aren’t common in Mexico, and would be probably classified as “negro”—black.

My two favorite domestic beers in Mexico are both oscuras and are both made by Grupo Modelo: Victoria and Negra Modelo. Victoria beer is a lighter amber color, while Negra Modelo is truly dark, though not technically a stout or porter. Both go down smooth without heavy flavors or aftertastes.

Both are widely available in stores and restaurants, although Victoria beer, like Corona, is perhaps slightly more common. Victoria also comes in more convenient containers, like the most affordable tallboys and caguamas (40-oz size returnable bottles. More on beer packaging below).

If Victoria wasn’t flavorful enough for you—if you want something with more caramel, chocolate, or general density—then try Leon, which I personally place in third after Victoria beer and Negra Modelo.

Two more major-label brands with even more flavor are Bohemia Oscura and the seasonal Noche Buena, which is only available in the months surrounding Christmas. (Noche Buena, literally “Good Night,” is Christmas Eve, and also the Poinsettia, the red and green Christmas plant, which is indigenous to Mexico and on the label.) Both are a little too chocolatey for my taste—I can drink one or two and that’s it. But there’re worth a try—some people love them, especially Noche Buena.

Or, go right to the microbrews described below, but they’ll cost you.

The most common alternative to Victoria beer, produced by the competing company, is Indio, which is usually the same price and available at the same places as Victoria. Also like Victoria, it’s common in tallboys and caguamas.

Indio is fine, and it has a strong presence at rock concerts and soccer games, meaning that sometimes you’ll have no choice if you want an oscura. Try it, and if you do so right after a Victoria, you might agree with me that Victoria beer is just a little bit better.

Clara: light beer in Mexico

Literally “clear,” claras include the beers that made Mexico famous—Dos Equis, Sol, and especially Corona. The brilliant marketing campaign for Corona showing the two transparent, sweating bottles with limes in their necks, sitting on a table on the beach before a calm ocean and bright blue sky, did wonders for this otherwise unremarkable beer.

Sure, it tastes fine, especially on that warm day as you sit in the shade of a seafood restaurant on the beach with your toes in the sand. But really, squeeze a lime into a Sol, Modelo, Pacifico, Tecate, or any other Mexican clara, and they all taste pretty much the same. Here’s a test—squeeze a lime into a Coors Light, and you’ll probably get the same effect.

Another note: In Mexico, they squeeze a slice of lime into beer, not lemon, and they never stick the whole thing in the bottle. More on that below.

As mentioned, I prefer dark beer in Mexico, but I won’t turn down a light one on a hot day either. Of the many Mexican claras, without a lime squeezed in, probably Modelo and Pacifico are the best, Modelo if only because you can buy it in cans for really cheap in nearly every neighborhood store.

After Corona from Grupo Modelo, the other most popular clara in Mexico is Sol from Cuauhtemoc-Moctezuma. They’re both typically available in the same places as their dark counterparts Victoria and Indio. “Corona” means crown, by the way—look for the king’s cap on the label, and “Sol” means sun.

Dos Equis, popular outside of Mexico, means “two Xs”: XX, which you can see on the label. Dos Equis has a clara and an amber. The clara’s light but distinctive taste is enjoyed by many on both sides of the border. It’s not my favorite; I consider it the Mexican Heineken, to compare it with another popular beer that doesn’t do much for me.

Tecate Light is the Bud Light of Mexico, loved by cowboy-hat wearing, big truck driving characters. (And yes, there is a Corona Light, Tecate Light, etc.—why they make light beers lighter, and if there is actually any difference, I have no idea.) Regular Tecate is far better than Tecate Light, especially from a tallboy as you stroll the beaches and marinas of Cabo San Lucas.

Yet another note: Public drinking is officially illegal in Mexico, although it’s tolerated in many beach towns. Don’t try it in Mexico City, however.

Other common ones for a hot day are Montejo, Superior, and the supposedly premium Carta Blanca. You could also pick up a six-pack of Barrilito, which come in funny, short bottles.

Finally, the domestic light beer in Mexico with the most flavor is Bohemia Weizen, the Bohemia beer with the blue label. It’s more expensive than everything else I’ve mentioned, but quite good—no need to squeeze a lime in.

Speaking of Bohemia beer, there’s also the strong Bohemia Obscura with the brown label, the average Bohemia Ambar, a redish pilsner, with the red label, and Bohemia Clasica, also a pilsner.

Try them all and tell me which ones you liked the best.

Microbrews in Mexico

There are now hundreds of microbreweries in Mexico, with more appearing regularly. The best place to find a wide selection is a specialty beer store like The Beer Box, or any somewhat upscale restaurant. They’re usually called cerveza artesanal or cerveza de autor.

I’ve tried many craft beers in Mexico, and they’re hit-or-miss. Some taste as good as any U.S. craft beer, especially the ones brewed in Baja California. Some taste like Corona with food coloring added. And sometimes—a real disappointment—something went wrong in the brewing process, and the bottle is far too pressurized. When you open it, beer foams out everywhere. So always have a large glass ready to pour it into.

One thing Mexican microbrews have in common is they’re uniformly expensive, especially when compared to the price of domestic mass-market beer in Mexico. You can expect to pay between 60-160 pesos for one 12-oz bottle, about three to eight U.S. dollars, and more in restaurants.

When you go to Beer Box or a restaurant with a selection of craft beer, try a few different ones, ask for advice, or check their descriptions. Two I like (that I can remember) are Comma Beer and Red Pig. To that end, here’s some beer vocabulary in Spanish to help you choose your craft beer.

- pale: rubia

- red: roja

- lúpulos: hops

- cebada: barley

- trigo: wheat

I love a good craft beer, but in general, my conscience won’t allow me to spend 60 pesos on one 12-oz bottle of beer, no matter how good it may be, when I could get two 40-oz bottles of Victoria beer for the same price.

Several craft beers have emerged as more affordable and more widely available than the rest, at least where I live. Some of the good ones are Minerva, Baja Brewing and Jabali. At about 40-50 pesos per bottle (about $2.5 USD), they’re at least half the price of other craft beers, although still double the price of a domestic.

Minerva, perhaps the cheapest and best-established craft beer in Mexico, is great. I love their stout, and their pale ale is good too. They also have an IPA, a lager, and something called a “tropilager,”—a “tropical lager”—all of which I haven’t tried yet. Their stout is good enough for me, making it my regular microbrew indulgence.

Besides beer stores like the Beer Box, you can find Minerva and other cheaper microbrews at big supermarkets like Chedraui or Wal-mart. (Yes, it’s a sad truth that in Mexico, Wal-Mart is one of the best places to buy imported beer, craft beers, wine, bourbon—not to mention peanut butter, cheddar cheese, and Ben and Jerry’s Ice Cream.)

The other affordable craft beers I’ve tried have been nothing to get excited about. Three others that you might find at a big supermarket are Cucapa, Day of the Dead, and Calavera—fancy packaging, tempting descriptions, but mediocre beer, and the danger of overly-pressurized bottles.

Tulum beer is another one available in convenience stores in the Mayan Riviera at a higher price than regular domestics but cheaper than most other craft beers. I remember Tulum beer as being pretty good, although my perception was certainly skewed by beautiful sunny weather compounded by profound thirst.

Beer Tours in Mexico

You have several options for beer tours in Mexico. It mostly depends on where you are.

Mexico City: Check out this Mexico City Tasting Tour and Craft Beer Experience to try some of the best beer in Mexico.

Cancun: On this Brewery Tour and Craft Beer Tasting in Cancun, Mexico, you’ll visit two breweries and sample craft beers made with local flavors and seasonal fruits.

Playa del Carmen: How about some tacos with your beer? Have a look at this Playa del Carmen Taco and Beer Tour with transportation.

Where to buy beer in Mexico

You can buy beer in Mexico practically anywhere, even on the side of the highway to take with you in the car. At concerts and soccer games, you don’t have to go looking for them—vendors regularly bring them right to you.

You can usually buy alcohol anytime you want, although in some parts of Mexico you can’t buy after midnight (or some late-night hour) or Sunday afternoon. Chain stores like the nationwide convenience store OXXO enforce this, locking their coolers, although many independent corner stores may not. Also, on election days and some Mexican holidays, the ley seca (the “dry law”) applies, meaning that sales of alcohol are prohibited, even in restaurants.

Tap beer in Mexico is not so common, even at bars and cantinas—usually they just give you bottles. Be careful with tap beer too. Unless you are at a reputable place that regularly cleans out the tubes that go from the barrel to the tap, you can get a wicked hangover from drinking tap beer. This has something to do with all those nasty old particles clinging to the tubes.

To save money, or to buy in bulk, you have two better options than the average family-run corner store. You’ll see OXXOs everywhere, and they have average prices and a good selection. What you may not notice is that, depending on the specific store, you can get a discount on certain beers (usually tallboys, called latas altas) when you buy four or more. You can look for signs or displays, ask the clerk, or just buy four and see what happens to the price.

Even better discounts are available at depositos, which are factory stores, also known as expendios. There are two types, corresponding to each major Mexican beer brand. These are the best places to buy caguamas—the refillable 40-oz bottles that are not only the best value, but the most environmentally friendly.

Tip: With recycled bottles (you’ll know them by their beat-up conditions and leftover label glue on the glass), don’t drink straight from the bottle. Look under the rim and you’ll probably see some leftover gunk that wasn’t properly washed off. Pour the beer into a glass, or wipe the rim down with a napkin. This also goes for soda, which is why at restaurants your Coke will always come with a glass.

You pay a deposit on the caguamas, so save the receipt. You can find them at OXXOs and small corner stores too, but they are much cheaper at depositos. At the moment the promotion is two for 60 pesos—about three USD, bottle deposit not included. Think about it—that’s 80 ounces of beer for the price of one microbrew at a beer store, or one 12-oz Corona at a fancy restaurant.

But it used to be even better. When I first moved to Mexico in 2010, there was a promotion for Indio—bring in three bottle caps, and a caguama of Indio was 10 pesos. Ten pesos—at the time it was about 80 U.S. cents!

Right about then, I happened to make friends with the guy who parked and washed cars in one of the parking lots near my house. He drank caguamas of Indio all day, every day, throwing the bottle caps into a big pile in the corner. Not because of the promotion; he just liked Indio. When I asked him if I could take some caps, he said, take as many as you want! Scoop them up!

So for my first six months in Mexico, I drank 80-cent 40s of pretty good beer. I thought, I’ve come to the right place.

Drinking beer Mexican style

You’ll rarely see a Mexican drink a beer straight, without any enhancements. Often so much goes into it that it barely tastes like beer. Me, despite the occasional squeeze of lime into a light beer on a hot day, I prefer beer in its natural state. So, I recommend nothing described below, except maybe the shrimp michelada for novelty’s sake.

Just like there’s salt and pepper on every dinner table in the U.S., there’s salt and lime on every Mexican table. They go on everything—tacos, soups, and of course beer. Mexicans squeeze a lime into the beer—they never shove the whole lime down the neck—and then sprinkle some salt on top. And it’s always a lime, never lemon. In fact I’ve only seen lemons for sale in certain regions of Mexico, and they’re a little different from the lemons you may be imagining.

A note on confusing vocabulary—limes (green) are called limones, and lemons (yellow) are called limas.

You can even order it this way—escarchada, which means “frosted.” You’ll get a frozen mug with salt on the rim and lime juice at the bottom—sometimes two or three fingers of lime juice—along with the bottle of beer, for an extra cost of a few pesos.

There’s something else about that lime and salt—if you happen to get a skunked or flat beer, the lime kills the bad taste. Lime is more than delicious, but a great equalizing force.

Lime and salt is only the beginning. The really Mexican way to drink beer is in a michelada. I’m not sure of the origin of this word, but it is similar to chela, which is the Mexican slang word for beer.

A michelada is basically a Bloody Mary with beer substituting vodka: lime, salt, tomato juice, and maybe something extra like hot sauce or Worcestershire sauce, which is called salsa inglesa—English sauce. The top of the container—usually a liter-sized paper cup—will be coated in dried ketchup-like hot sauce and salt, looking vaguely like the pieces of broken glass sunken into the top of a concrete wall for security, seen on modest urban homes throughout Mexico.

You can even buy cans of pre-made micheladas, or with just the lime and salt already mixed in.

You can get some wild micheladas too, sometimes full of seafood like shrimp or oysters or slices of fruit and vegetables like mango or jicama. These aren’t bad, actually, but are more of a meal, or an experience, than a refreshment.

Another option is a cubana, which skips the tomato sauce and loads up with Worcestershire sauce until you can’t even taste the beer. Some places commit the further blasphemy of putting sugary fruit-flavored powder (mango, pineapple, etc.) in the beer or on the rim, presumably for the younger crowd.

Besides restaurants and town fairs, you can also find these for sale on the side of the road from convenience stores or little stands. You’ll know they serve micheladas when you see a bunch of caguama bottles lined up and big paper cups on a table in front of the store.

I don’t drink micheladas or these other concoctions, and I don’t know many foreigners who do, but actually they’re not as bad as they sound. Because of all these options, if you just want your beer and nothing else, order it sola—literally “alone.”

But try a michelada, if for nothing else than the experience. I had them fairly often when I first moved here, although now I can’t remember the last time I’ve had one. Probably at a crowded town festival with bouncy banda music playing.

You’ll know you’ve been drinking micheladas at one of these events, because the next day you’ll wake up to your shirt covered in little red horizontal lines from all the times someone bumped into your beer, and the rim of dried hot sauce and salt hit your chest.

At your next Mexican party, look around for the mark of the michelada. If you see one, I hope you’ll remember this article and laugh.

This page contains affiliate links, which means I earn a small commission if you purchase something after clicking a link on this site. I receive this commission at no additional cost to you.

Cenote Scuba Diving in the Mayan Riviera, Mexico

I never expected that some of the best diving in Mexico would be cenote diving.

On a steaming tropical morning, the van turned off the highway onto a bumpy two-track. The jungle was a thick wall of green, with leaves reaching out from every direction. Branches scratched windows and scuba tanks knocked against each other under my seat.

The short sand road ended at a small clearing in the jungle of bamboo huts and cinderblock storage sheds. We stepped out of the van into a swarm of mosquitos. I pulled the wetsuit over my shoulders, thinking it was surely the first time I’d taken a van to go scuba diving. But this wouldn’t be regular scuba diving. This was cenote diving.

What’s a cenote, you ask? Well, there are no mountains or large above-ground rivers on the Yucatan in southeastern Mexico. The entire peninsula is like an enormous limestone sponge, jagged and bumpy but generally flat straight across. Like a sponge, it’s full of holes, and the holes are full of clear freshwater. The holes are called cenotes—sinkholes that formed when the crusty surface collapsed and exposed the water beneath.

The Yucatan Peninsula is no simple sponge, however, and cenotes are no simple holes. They lead to a huge network of ancient caverns connected by underground rivers. The caverns weren’t formed by the water, but were flooded 11,700 years ago when the most recent ice age ended.

Humans probably lived in them before then, which is why skeletons, fire pits, and artifacts have been found throughout. And before it became limestone, it was a reef, so if you look closely you can see shells and coral mixed in with the rock.

To sign up for a cenote diving trip online, check out this tour for certified divers.

Want to try cenote scuba diving but don’t have experience (or need a refresher)? Check out this popular cenote tour: Cenote Diving for First-Time Divers and for Refresher Dives in Tulum.

If you’re not a diver but still want to visit Cenote Dos Ojos (and the Mayan ruins of Tulum), take a look at this Tulum & Cenote Day Trip.

The unique geology of the Yucatan isn’t even its best-known feature. Sure, the prime attraction may be powdery white-sand beaches and some of the best diving in Mexico, but the region is also famous for the Mayans, the ancient civilization that built great cities like Chichen Itza and Tulum.

This civilization wouldn’t have been possible without the abundance of freshwater underground, and many archeologists believe that its mysterious decline and collapse was caused by some disturbance to the water supply.

Today, thousands of visitors to Cancun or Playa del Carmen never visit a cenote, preferring unlimited drinks at the resort pool. They never realize that they’re visiting a geologically unique part of the world, with beauty everywhere—even underground.

There are more than 6,000 cenotes in the Yucatan Peninsula, most lost deep in the jungle, visited by no one. Some are little more than a narrow crack or hole in the earth. Others are at the bottom of lakes, only visible by the circular shadow below the surface of the water, like in Kaan Luum near Tulum.

Go to Kaan Luum and several cenotes on this affordable tour that also includes lunch.

Many cenotes developed for tourism resemble open ponds surrounded by rocky banks covered in vegetation, where you can swim, snorkel, or experience some of the best scuba diving in Mexico. I’ve gone swimming in many cenotes during the years I’ve spent traveling the Yucatan, but I hadn’t yet gone cenote scuba diving. Now was the time.

The first dive would be Angelita, a small cenote south of Tulum. There’s not much to attract non-divers to Angelita, as it’s just a circle of water lined with jagged limestone, no larger than a tennis court. Unlike cenotes popular with swimmers or snorkelers, there are no rocky overhangs to jump off, nor shallow entrances to half-submerged caverns, accessible by holding your breath. Instead, Angelita goes deep, straight down, and with a few surprises.

Although there are other cenotes for deep dives, such as Cenote El Pit, Angelita is remarkable for its halocline, a yellow cloud of hydrogen sulfate at 30 meters. It’s caused by leakage of decomposing plant matter from nearby Kaan Luum lake, which has a cenote in the middle and shares the same groundwater as Angelita. Above the murky halocline is transparent freshwater, and below is dark salt water. Dive weights made of lead eventually turn black due to the sulfur in Angelita’s halocline.

Slapping mosquitos, we geared up next to the van and walked down a rocky footpath through the jungle to a wooden staircase and platform next to the water, where we strapped on our flippers and jumped in. There were four of us—three divers and Marco, the dive master.

Once in the water, we began our slow descent to a large bump of soil at 25 meters, covered in fallen branches. The dull yellow halocline surrounded it like clouds around a hill, making it look like an island. The bare branches gave it a creepy appearance, like fog over a nighttime graveyard in an old horror movie.

Occasionally a grey, lethargic fish swam by. Marco told me later that while cave diving in deeper sections, he’d seen fish with no eyes.

We descended in a spiral around the island, stopping just above the halocline. Our flippers dipped into it, out of sight. Here we formed a circle before another descent.

Exhaling fully, we sank into the yellow cloud, flippers first. My body disappeared below me. There was no seeing through the halocline. Soon it was up to my neck, then my chin, and then it reached my goggles.

The rotten-egg sulfur taste filled my mouth and nose. The upper edge of the halocline looked like the sides of a cloud seen from an airplane. Deeper down it resembled thick yellow cotton. The beam from my flashlight dispersed into the yellow and went no farther.

Suddenly I passed through the cloud into total darkness. The flashlight shone forward but illuminated nothing. It was the same in every direction—I couldn’t even see the yellow above my head.

A light flashed to my right—Marco making sure everyone was fine. I made the “ok” gesture with my hands. He signaled me to follow him. I shone my flashlight on the backs of his flippers, following as we descended nine meters lower than the halocline, to our maximum depth of 39 meters (128 feet). Next we slowly swam up and reentered the halocline. You couldn’t see through the yellow, but looking up toward sunlight meant that it was lit with an eerie glow.

I was the first to cross the halocline back into freshwater, so I watched the other divers appear like swamp-things emerging from a yellow mist. I paddled into an upside-down position, exhaled, and dipped my face into it, watching the yellow change from semi-transparent to full-on cloud.

I swam along the halocline with my body half above, half-below it. It didn’t dissipate like a handful of fine sand released underwater would, but stayed together, parting only slightly as I swam through it.

In scuba diving, the deeper you go, the more air you use, so you can’t spend much time at 30 meters (about 100 feet) or deeper. Marco signaled for us to follow and we began to ascend, again in a spiral but this time closer to the cenote walls. They were mostly bare rock and dirt with a few green plants hanging on.

Marco swam into a narrow hole to enter a passage that went in a short loop to a nearby exit. He’d told us about this small cavern in his briefing by the van earlier. This would be a good buoyancy test, as later that morning we’d be squeezing through much narrower passages full of delicate stalactites in the next cenote, Dreamgate.

Buoyancy refers to a diver’s ability to maintain an even level under the water. Many factors influence it, especially breathing. When you breathe in, filling your lungs with air like you’d fill up a balloon, you naturally begin to float, and when you breathe out, the release of air makes you sink. Another factor is motion—when you move your arms or legs, you start to rise.

Therefore, the best way to control buoyancy is to breathe slowly and move as little as possible. You have to be extra careful in tight spaces, because if you rise too quickly your tank will bang on the rock above, damaging it. I found controlling my buoyancy in the cenote fairly easy, especially compared to the open ocean with its unpredictable currents.

One of the other divers, a girl from Vietnam, had trouble controlling her buoyancy and consequently decided not to go to the next dive, which was for experts only. Both cenotes required an advanced certification, but having an advance certification doesn’t always mean that you are an expert. You learn how to control factors like buoyancy through experience, not through a certification course.

She’d be in Tulum for several more days anyway and would go to Dos Ojos, another, less challenging and much more popular spot for cenote scuba diving. After finishing our dive at Angelita, we dropped her off in Tulum and continued north to Dreamgate.

The day before, the guy at the dive shop had told me that he usually recommends Dos Ojos for first-time cenote divers like me, along with Angelita for its uniqueness. He showed me a little book with descriptions and maps of the main scuba diving cenotes near Tulum.

The usual plan was three tanks in two cenotes: one tank on a deep dive like Angelita or Cenote El Pit, and then two tanks at a cenote with two different routes through caverns, like Dos Ojos. I’d been snorkeling at Dos Ojos and knew it was beautiful, but I said, “Dos Ojos looks great, but which cenote would you say is the best around here?”

“Dreamgate, no question,” he said. “But it’s not in the book.” He took out his phone and showed me some pictures: the strange radiance of underwater flashlights illuminating a ceiling crowded with long, lumpy stalactites, while stalagmites reached upwards from the floor and a horizontal diver drifted by.

“It’s for experienced divers only. Some passages are really tight and you need complete control of your buoyancy. If not, you may break off a stalactite, or you may kick up some sand. Both are really bad. When you kick up sand, the people following you won’t be able to see anything.”

“Sign me up,” I said.

Marco repeated these same warnings as he drove the van to Dreamgate on the highway between Tulum and Playa del Carmen. There was no sign for the turnoff, just a nondescript path that twisted and turned deep into the jungle. At the end of the path was some space for parking and a doorless concrete outhouse, nothing else, unlike Angelita which had a few buildings and some staff hanging around.

The cenote was about as big around as Angelita but oval and surrounded by higher cliffs. You could see that the water was shallow enough to stand on the sandy bottom, and that under the cliffs was a gap where the water went deeper underground.

A staircase led to a platform over the water. Marco lowered the tanks to the platform using a rope, since the stairs were too steep and slippery for us to walk down with the tanks on. We geared up on the platform, got into the water, and floated on our backs, looking up at the trees and vines hanging over the tall cliffs above.

We would do two dives through different caverns, changing tanks between them. Our maximum depth would be only six meters (20 feet), so we’d have plenty of air for both routes, which were marked with ropes underwater. The three of us in a line, with Marco in front, followed the rope down along the sandy bottom and into the caverns.

It was spectacular. Stalactites (the ones that hang down) and stalagmites (the ones that come up) were everywhere, populating the passages like skyscrapers on Manhattan. Some parts had so many that they looked like the edge of a roof covered with icicles. Some were no larger than your index finger, and some twisted and bulged like a boa constrictor swallowing a deer.

As warned, we had to swim carefully through narrow passages where any sudden movement would stir up the sand below or smash the rocks above. You could see how some stalactites had already been broken off in these sections.

As we got deeper, we entered a few wide-open chambers. A strange light came from the end of one, and as it got brighter I realized that it must be another group of divers. They swam into view at the other end of the chamber, looking like astronauts in outer space, fully horizontal and holding flashlights in front of them. The water totally filled the chambers, though if I looked up I could see trapped bubbles of air among the jagged rocks above.

We entered a chamber high enough that it had several meters of air above. We went to the surface and took off our masks. Roots from alamo trees dangled from the rocky ceiling like tangled dreadlocks, their tips barely reaching the surface of the water. “Let’s all turn off our flashlights,” I said. The darkness was complete. The only sound was water dripping all around.

From there we turned around and slowly retraced our route. After a break, the second dive down another cavern was similar to the first, only with different structures, different passages, and different chambers.

After the dive, Marco told us that he’d once seen the remains of a fire pit there, presumably from the previous ice age before the caverns flooded, when humans used to live in them. He said you could find bones too, sometimes from ancient animals like mastodons and long-toothed cats, but this happened on much deeper cave diving explorations.

In fact, in early 2018, several human skeletons were found in an exploration of the nearby Sac Actun system. This cave diving exploration also confirmed that the San Actun and Dos Ojos systems (which includes Dreamgate) are actually connected, making it the largest cave system in the world.

Thinking about all the extra air left in our tanks, I asked Marco why we hadn’t gone farther, into one of the deeper sections where we might have found a fire pit or eyeless fish.

“You can’t leave the guidelines,” he replied. “There are big fines if you do. Plus, it’s extremely dangerous. You can get lost in a second, and when your air runs out…” He emphasized this point with a long, airy whistle.

“But you’ve gone deeper, right?”

“Sure, many times.” He tapped the tank still strapped to his back. “For cave diving we always bring two tanks, one strapped to each side of you, and with special gas. Having them on your sides makes it harder to keep your buoyancy, but it’s necessary that way, so you can fit into the really tight spaces.”

“And you need a cave diving certification?”

“Yes, but that’s not enough. You need one for the blended gas too, and rescue certifications, and others. I did it so long ago I don’t exactly remember. You need to be a divemaster, at least.”

“Could I do the certifications at your shop?”

He smiled. “You could, but it would take a while. It took me years.”

“Some day,” I said.

Once we were back in the van, the other diver, well-traveled Max from Australia, told me that it was one of the coolest things he’d ever done—not just the best diving in Mexico, but one of the coolest things, period.

Marco laughed and lit his thousandth cigarette. “I never dive in the ocean,” he said, “only cenotes.” He complemented us on our buoyancy—not one chipped rock or stirred-up cloud of sand all morning.

I agreed with Max. But I couldn’t decide which was better—the creepy descent through the yellow halocline in Angelita, or the outer-space cavern diving exploration of Dreamgate. I still can’t decide.

IF YOU WANT TO GO CENOTE DIVING IN MEXICO

Visit a dive shop first. There are dive shops all over the Mayan Riviera that arrange cenote diving, but the ones in Tulum are closer to some of the best cenotes, and therefore more convenient and probably cheaper. I went with Space Dive, also called Dive and Snorkel Tulum, and I recommend them highly. Their office is on the main road in Tulum about a block from the ADO bus station.

Or, if you don’t have time to visit a dive shop, or what to get an idea of what to expect before you arrive in the Mayan Riviera, you can check out a cenote diving tour like this one.

If you don’t scuba dive but want to visit a cenote, you don’t need a guide or dive shop. Just show up. There are numerous cenotes between Playa del Carmen and Tulum, including a cluster of six across the street from the Barceló resort immediately south of Playa del Carmen. Also, to save time and avoid confusion, you can choose to take a tour to the cenotes of the Mayan Riviera.

There are also many inland, such as near Valladolid and Mérida. Close to Mérida, next to the small town of Cuzuma, are three cenotes that you get to by taking a horse-drawn cart on train tracks through an old sugarcane plantation, a fun and unique experience.

To visit the Cuzuma cenotes on a tour from Merida, check out this highly-rated Full-Day Cuzamá Cenote Tour.

Two good ones near Tulum are Dos Ojos (with Cenote El Pit just a little deeper in the jungle beyond) and Gran Cenote. These and others like them are much smaller (and cheaper) operations than the massive adventure parks like Xel-Ha and Rio Secreto that have advertisements everywhere.

Thanks for reading my article about cenote scuba diving in Mexico. I definitely think the best diving in Mexico takes place in fresh water underground. If you agree, please leave a comment below.

Underwater photography by Gilles from Switzerland

This page contains affiliate links, which means I earn a small commission if you purchase something after clicking a link on this site. I receive this commission at no additional cost to you.